Recognising the role of indigenous peoples in protecting nature

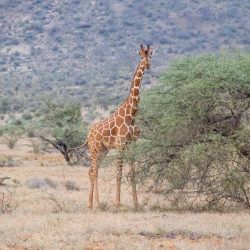

From the Aboriginal and the Torres Strait Islander peoples of Australia, to the El Molo and Dasanach tribes of Northern Kenya, indigenous communities are a formidable force who are quietly, but quite remarkably, protecting vital ecosystems that ensure the health of our planet and our survival as humanity.

African traditional customs and belief systems hold deep respect and regard for nature - positioning people and the environment as two intrinsically connected entities. And that’s just the tip of the ice berg - IPLCs bring a lot more to the table than what meets the eye: over 6950 languages, incredible generational knowledge, strong systems of legal jurisdiction around environmental justice as well as traditional practices that are critical to saving our flora and fauna species from climate change and biodiversity loss. These practices and vast ancestral knowledge are one of the many reasons why IPLC groups must be genuinely engaged as partners to address climate change adaptation efforts.

Despite all these contributions, the picture has not been rosy for some of these marginalised and often forgotten peoples. Lately, their lives have revolved around constant battles with an array of challenges that threaten their livelihoods and lifestyles that they have practiced for millennia. In Tanzania, we have all heard of the Loliondo Maasai evictions where the rights of pastoralist groups have been violated by stakeholders with economic interests in tourism development. In Ethiopia, the development of the Gibe III dam will significantly reduce the down flow volume (quantity) and quality of the Omo River, eventually threatening the ecological integrity of the Omo Valley ecosystem.

From the Ethiopian Government’s standpoint, the project made total sense. It was a no brainer as the Horn of Africa nation has been grappling with energy challenges with frequent shortage and load shedding to serve its growing population of 120 million people. For the indigenous communities of Southern Ethiopia such as the Mursi, Karo and the Nyangatom, their livelihoods are on the line - especially for fishing, livestock keepers and crop farmers cultivating maize, beans and sorghum for their families. The Omo River is the main tributary to the world’s largest desert lake, Lake Turkana. This water body supports other fishing and livestock keeping communities downstream in Northern Kenya such as the Turkana, Gabra, Dasanach and El Molo. The construction of these mega-infrastructural projects will not only degrade the quality of the lives of these peoples but also impact the frontline protectors of nature. This poses an existential threat to farmers, fishermen and cattle keepers who reside within the Omo Delta landscape, the Lake Turkana Basin in Kenya and its environs. These 2 scenarios adequately explain why IPLC groups have often turned up at key environmental summits totally angered and unrestrained in the vitriol they hurl at their respective governments and private sector leaders for their lack of affirmative action.

Light at the end of the tunnel?

Enough of the dull image, it’s time we appreciate the glass as half full. Let’s picture what the ideal situation may look like if we had our way. Ideals may not often happen overnight especially in conservation but I’m a dealer in hope. I strongly believe that if we all unite and sing from the same hymn book, we can address these threats and find an amicable solution out of this complex conundrum. Every year on the 9th of August, the world marks the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples to promote the rights of indigenous peoples around the globe, celebrate their vibrant cultures, learn from their vast ancestral knowledge systems and appreciate their role as the primary custodians of the some of the planet’s most important biodiversity resources.

On a day like today, we need to do a bit more than marvelling at the unique dances and cultures of indigenous peoples. It’s time we walk the talk. What does this mean? It means we must put a halt to the violations of the rights of the world’s marginalised communities and respect their land tenure rights as well as rights for self determination. Beyond that, global leadership, governments and donors must start to position indigenous communities as critical partners, not beneficiaries, to the effective implementation of key biodiversity agreements such as the Kunming Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and the Kigali Call to Action.

Last year in Kigali, Rwanda, Africans from all walks of life gathered at the Africa Protected Areas Congress #APAC2022 to discuss the most pressing environmental challenges facing the continent’s natural real estate in order to chart a sustainable path forward. Stakeholder groups from governments, national youth movements, civil society institutions, the private sector, NGOs, finance actors, women and IPLC institutions thrashed out ideas on inclusive people-centred approaches to address the threats facing people and nature in Africa. Across the week-long historic congress (#APAC2022), there was one resounding message that came from the summit: putting people at the centre of effective and equitable conservation. The Kigali Call to Action forms the African blue print of the aspirations of Africans from a socio-economic development standpoint. Within the binding document that was adopted during the 18th session of the African Ministerial Conference on the Environment AMCEN 2022 in Ghana, Ministers of Environment from different jurisdictions across the continent unanimously agreed to domesticate the Kigali Call to Action into their national development plans and strategies.

With the Africa Climate Summit around the corner in September 2023, Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities are putting all their hopes in African leaders to act on the deliberations that were agreed in Kigali last year. The dialogue at the #AfricaClimateSummit must address inclusive green growth and climate finance solutions that intentionally engage local stakeholders such as IPLC groups, women and the youth on climate change adaptation efforts.